Running and Quitting

Overview

Teaching: 6 min

Exercises: 2 minQuestions

How can I run Python programs?

Objectives

Launch the JupyterLab server.

Create a Jupyter notebook.

Shutdown the JupyterLab server.

Create and run Python cells in a notebook.

Getting Started with JupyterLab

JupyterLab is included as part of the Anaconda Python distribution. If you have not already installed the Anaconda Python distribution, see the setup instructions for installation instructions.

Starting JupyterLab

You can start the JupyterLab server through the command line or through an application called

Anaconda Navigator. Anaconda Navigator is included as part of the Anaconda Python distribution.

macOS - Command Line

To start the JupyterLab server you will need to access the command line through the Terminal. There are two ways to open Terminal on Mac.

- In your Applications folder, open Utilities and double-click on Terminal

- Press Command + spacebar to launch Spotlight. Type

Terminaland then double-click the search result or hit Enter

After you have launched Terminal, type the command to launch the JupyterLab server.

$ jupyter lab

Windows Users - Command Line

To start the JupyterLab server you will need to access the Anaconda Prompt.

Press Windows Logo Key and search for Anaconda Prompt, click the result or press enter.

After you have launched the Anaconda Prompt, type the command:

$ jupyter lab

Anaconda Navigator

To start a JupyterLab server from Anaconda Navigator you must first start Anaconda Navigator (click for detailed instructions on macOS, Windows, and Linux). You can search for Anaconda Navigator via Spotlight on macOS (Command + spacebar), the Windows search function (Windows Logo Key) or opening a terminal shell and executing the anaconda-navigator executable from the command line.

After you have launched Anaconda Navigator, click the Launch button under JupyterLab. You may need

to scroll down to find it.

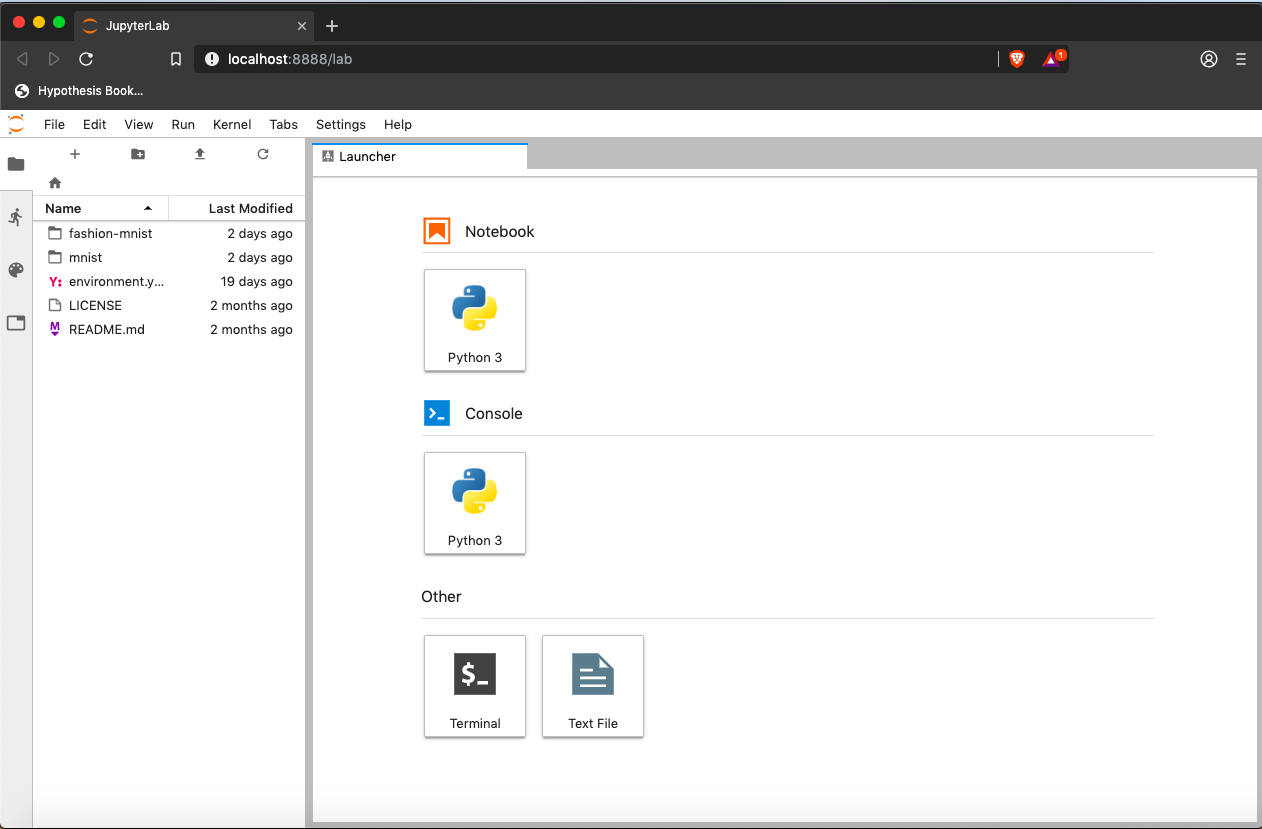

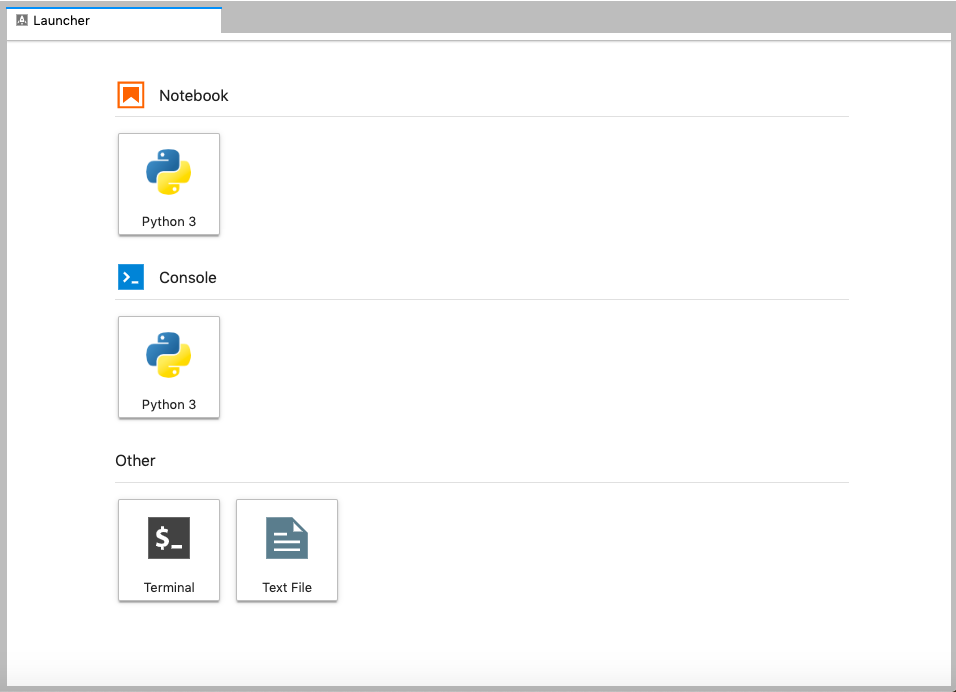

Here is a screenshot of a JupyterLab landing page that should be similar to the one that opens in your default web browser after starting the JupyterLab server on either macOS or Windows.

The JupyterLab Interface

JupyterLab has many features found in traditional integrated development environments (IDEs) but is focused on providing flexible building blocks for interactive, exploratory computing.

The JupyterLab Interface consists of the Menu Bar, a collapsable Left Side Bar, and the Main Work Area which contains tabs of documents and activities.

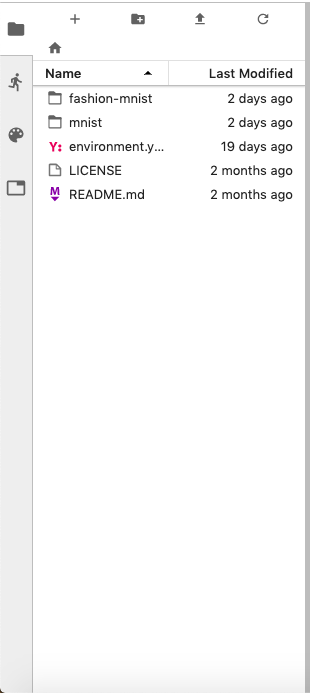

Left Sidebar

The left sidebar contains a number of commonly used tabs, such as a file browser (showing the contents of the directory where the JupyterLab server was launched), a list of running kernels and terminals, the command palette, and a list of open tabs in the main work area. A screenshot of the default Left Side Bar is provided below.

The left sidebar can be collapsed or expanded by selecting “Show Left Sidebar” in the View menu or by clicking on the active sidebar tab.

Main Work Area

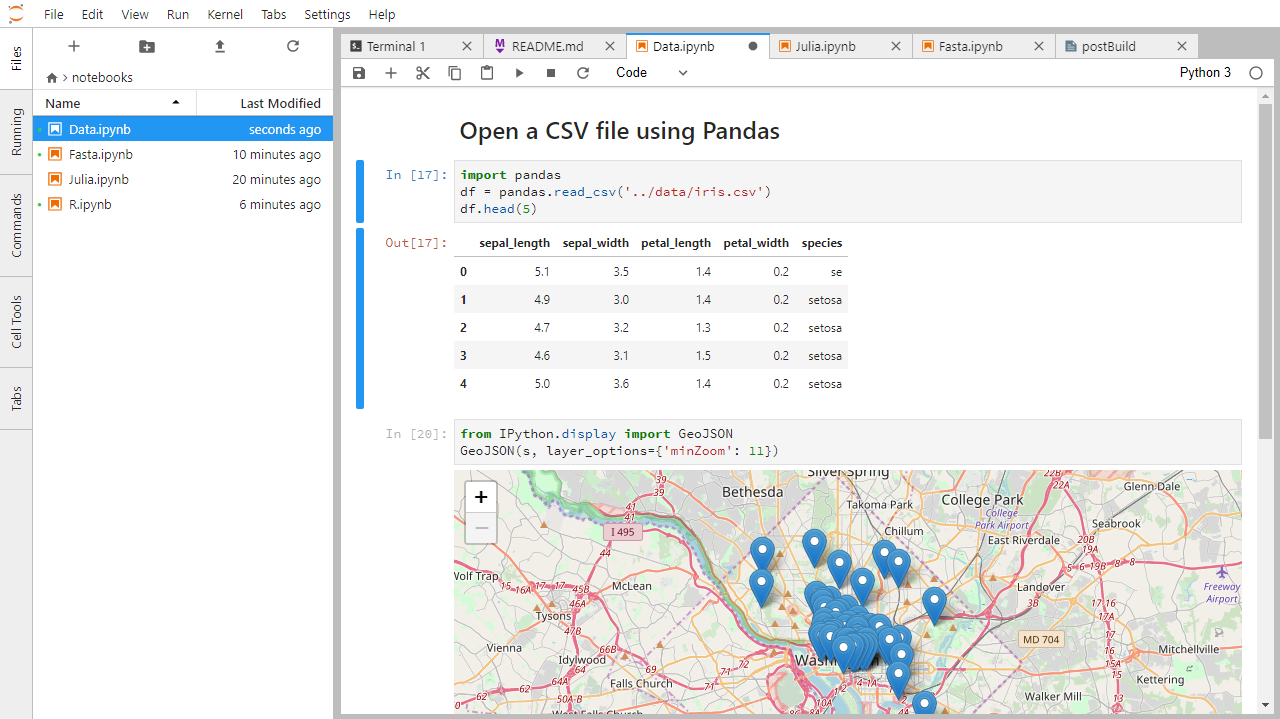

The main work area in JupyterLab enables you to arrange documents (notebooks, text files, etc.) and other activities (terminals, code consoles, etc.) into panels of tabs that can be resized or subdivided. A screenshot of the default Main Work Area is provided below.

Creating a Jupyter Notebook

To open a new notebook click the Python 3 icon under the Notebook header in the Launcher tab in the main work area. You can also create a new notebook by selecting New -> Notebook from the File menu in the Menu Bar.

A note on Jupyter notebooks.

- Notebook files have the extension

.ipynbto distinguish them from plain-text Python programs.

Below is a screenshot of a Jupyter notebook running inside JupyterLab. If you are interested in more details, then see the official notebook documentation.

Code vs. Text

Jupyter mixes code and text in different types of blocks, called cells. We often use the term “code” to mean “the source code of software written in a language such as Python”. A “code cell” in a Notebook is a cell that contains software; a “text cell” is one that contains ordinary prose written for human beings.

The Notebook has Command and Edit modes.

- If you press Esc and Return alternately, the outer border of your code cell will change from gray to blue.

- These are the Command (gray) and Edit (blue) modes of your notebook.

- Command mode allows you to edit notebook-level features, and Edit mode changes the content of cells.

- When in Command mode (esc/gray),

- The b key will make a new cell below the currently selected cell.

- The a key will make one above.

- The x key will delete the current cell.

- The z key will undo your last cell operation (which could be a deletion, creation, etc).

- All actions can be done using the menus, but there are lots of keyboard shortcuts to speed things up.

Command Vs. Edit

In the Jupyter notebook page are you currently in Command or Edit mode?

Switch between the modes. Use the shortcuts to generate a new cell. Use the shortcuts to delete a cell. Use the shortcuts to undo the last cell operation you performed.Solution

Command mode has a grey border and Edit mode has a blue border. Use Esc and Return to switch between modes. You need to be in Command mode (Press Esc if your cell is blue). Type b or a. You need to be in Command mode (Press Esc if your cell is blue). Type x. You need to be in Command mode (Press Esc if your cell is blue). Type z.

Use the keyboard and mouse to select and edit cells.

- Pressing the Return key turns the border blue and engages Edit mode, which allows you to type within the cell.

- Because we want to be able to write many lines of code in a single cell, pressing the Return key when in Edit mode (blue) moves the cursor to the next line in the cell just like in a text editor.

- We need some other way to tell the Notebook we want to run what’s in the cell.

- Pressing Shift+Return together will execute the contents of the cell.

- Notice that the Return and Shift keys on the right of the keyboard are right next to each other.

More Math

What is displayed when a Python cell in a notebook that contains several calculations is executed? For example, what happens when this cell is executed?

7 * 3 2 + 1Solution

Python returns the output of the last calculation.

3

Closing JupyterLab

- From the Menu Bar select the “File” menu and then choose “Shut Down” at the bottom of the dropdown menu. You will be prompted to confirm that you wish to shutdown the JupyterLab server (don’t forget to save your work!). Click “Shut Down” to shutdown the JupyterLab server.

- To restart the JupyterLab server you will need to re-run the following command from a shell.

$ jupyter lab

Closing JupyterLab

Practice closing and restarting the JupyterLab server.

Key Points

Use the Jupyter Notebook for editing and running Python.

The Notebook has Command and Edit modes.

Use the keyboard and mouse to select and edit cells.

Variables and Assignment

Overview

Teaching: 8 min

Exercises: 4 minQuestions

How can I store data in programs?

Objectives

Write programs that assign scalar values to variables and perform calculations with those values.

Correctly trace value changes in programs that use scalar assignment.

Use variables to store values.

- Variables are names for values.

- In Python the

=symbol assigns the value on the right to the name on the left. - The variable is created when a value is assigned to it.

-

Here, Python assigns an age to a variable

ageand a name in quotes to a variablefirst_name.age = 42 first_name = 'Ahmed' - Variable names

- can only contain letters, digits, and underscore

_(typically used to separate words in long variable names) - cannot start with a digit

- are case sensitive (age, Age and AGE are three different variables)

- can only contain letters, digits, and underscore

- Variable names that start with underscores like

__alistairs_real_agehave a special meaning so we won’t do that until we understand the convention.

Use print to display values.

- Python has a built-in function called

printthat prints things as text. - Call the function (i.e., tell Python to run it) by using its name.

- Provide values to the function (i.e., the things to print) in parentheses.

- To add a string to the printout, wrap the string in single or double quotes.

- The values passed to the function are called arguments

print(first_name, 'is', age, 'years old')

Ahmed is 42 years old

printautomatically puts a single space between items to separate them.- And wraps around to a new line at the end.

Variables must be created before they are used.

- If a variable doesn’t exist yet, or if the name has been mis-spelled, Python reports an error. (Unlike some languages, which “guess” a default value.)

print(last_name)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-1-c1fbb4e96102> in <module>()

----> 1 print(last_name)

NameError: name 'last_name' is not defined

- The last line of an error message is usually the most informative.

- We will look at error messages in detail later.

Variables can be used in calculations.

- We can use variables in calculations just as if they were values.

- Remember, we assigned the value

42toagea few lines ago.

- Remember, we assigned the value

age = age + 3

print('Age in three years:', age)

Age in three years: 45

Use an index to get a single character from a string.

- The characters (individual letters, numbers, and so on) in a string are

ordered. For example, the string

'AB'is not the same as'BA'. Because of this ordering, we can treat the string as a list of characters. - Each position in the string (first, second, etc.) is given a number. This number is called an index or sometimes a subscript.

- Indices are numbered from 0.

- Use the position’s index in square brackets to get the character at that position.

atom_name = 'helium'

print(atom_name[0])

h

Use a slice to get a substring.

- A part of a string is called a substring. A substring can be as short as a single character.

- An item in a list is called an element. Whenever we treat a string as if it were a list, the string’s elements are its individual characters.

- A slice is a part of a string (or, more generally, any list-like thing).

- We take a slice by using

[start:stop], wherestartis replaced with the index of the first element we want andstopis replaced with the index of the element just after the last element we want. - Mathematically, you might say that a slice selects

[start:stop). - The difference between

stopandstartis the slice’s length. - Taking a slice does not change the contents of the original string. Instead, the slice is a copy of part of the original string.

atom_name = 'sodium'

print(atom_name[0:3])

sod

Use the built-in function len to find the length of a string.

print(len('helium'))

6

- Nested functions are evaluated from the inside out, like in mathematics.

Python is case-sensitive.

- Python thinks that upper- and lower-case letters are different,

so

Nameandnameare different variables. - There are conventions for using upper-case letters at the start of variable names so we will use lower-case letters for now.

Use meaningful variable names.

- Python doesn’t care what you call variables as long as they obey the rules (alphanumeric characters and the underscore).

flabadab = 42

ewr_422_yY = 'Ahmed'

print(ewr_422_yY, 'is', flabadab, 'years old')

- Use meaningful variable names to help other people understand what the program does.

- The most important “other person” is your future self.

Predicting Values

What is the final value of

positionin the program below? (Try to predict the value without running the program, then check your prediction.)initial = 'left' position = initial initial = 'right'Solution

'left'The

initialvariable is assigned the value'left'. In the second line, thepositionvariable also receives the string value'left'. In third line, theinitialvariable is given the value'right', but thepositionvariable retains its string value of'left'.

Slicing practice

What does the following program print?

atom_name = 'carbon' print('atom_name[1:3] is:', atom_name[1:3])Solution

atom_name[1:3] is: ar

Key Points

Use variables to store values.

Use

Variables must be created before they are used.

Variables can be used in calculations.

Use an index to get a single character from a string.

Use a slice to get a substring.

Use the built-in function

lento find the length of a string.Python is case-sensitive.

Use meaningful variable names.

Data Types and Type Conversion

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 7 minQuestions

What kinds of data do programs store?

How can I convert one type to another?

Objectives

Explain key differences between integers and floating point numbers.

Explain key differences between numbers and character strings.

Use built-in functions to convert between integers, floating point numbers, and strings.

Every value has a type.

- Every value in a program has a specific type.

- Integer (

int): represents positive or negative whole numbers like 3 or -512. - Floating point number (

float): represents real numbers like 3.14159 or -2.5. - Character string (usually called “string”,

str): text.- Written in either single quotes or double quotes (as long as they match).

- The quote marks aren’t printed when the string is displayed.

Use the built-in function type to find the type of a value.

- Use the built-in function

typeto find out what type a value has. - Works on variables as well.

print(type(52))

<class 'int'>

fitness = 'average'

print(type(fitness))

<class 'str'>

Types control what operations (or methods) can be performed on a given value.

- A value’s type determines what the program can do to it.

print(5 - 3)

2

print('hello' - 'h')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-2-67f5626a1e07> in <module>()

----> 1 print('hello' - 'h')

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for -: 'str' and 'str'

You can use the “+” operator on strings.

- “Adding” character strings concatenates them.

full_name = 'Ahmed' + ' ' + 'Walsh'

print(full_name)

Ahmed Walsh

Must convert numbers to strings or vice versa when operating on them.

- Cannot add numbers and strings.

print(1 + '2')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-4-fe4f54a023c6> in <module>()

----> 1 print(1 + '2')

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

- Not allowed because it’s ambiguous: should

1 + '2'be3or'12'? - Some types can be converted to other types by using the type name as a function.

print(1 + int('2'))

print(str(1) + '2')

3

12

Can mix integers and floats freely in operations.

- Integers and floating-point numbers can be mixed in arithmetic.

- Python 3 automatically converts integers to floats as needed.

print('half is', 1 / 2.0)

print('three squared is', 3.0 ** 2)

half is 0.5

three squared is 9.0

Variables only change value when something is assigned to them.

- If we make one cell in a spreadsheet depend on another, and update the latter, the former updates automatically.

- This does not happen in programming languages.

variable_one = 1

variable_two = 5 * variable_one

variable_one = 2

print('first is', variable_one, 'and second is', variable_two)

first is 2 and second is 5

- The computer reads the value of

firstwhen doing the multiplication, creates a new value, and assigns it tosecond. - After that,

seconddoes not remember where it came from.

Automatic Type Conversion

What type of value is 3.25 + 4?

Solution

It is a float: integers are automatically converted to floats as necessary.

result = 3.25 + 4 print(result, 'is', type(result))7.25 is <class 'float'>

Choose a Type

What type of value (integer, floating point number, or character string) would you use to represent each of the following? Try to come up with more than one good answer for each problem. For example, in # 1, when would counting days with a floating point variable make more sense than using an integer?

- Number of days since the start of the year.

- Time elapsed from the start of the year until now in days.

- Serial number of a piece of lab equipment.

- A lab specimen’s age

- Current population of a city.

- Average population of a city over time.

Solution

The answers to the questions are:

- Integer, since the number of days would lie between 1 and 365.

- Floating point, since fractional days are required

- Character string if serial number contains letters and numbers, otherwise integer if the serial number consists only of numerals

- This will vary! How do you define a specimen’s age? whole days since collection (integer)? date and time (string)?

- Choose floating point to represent population as large aggregates (eg millions), or integer to represent population in units of individuals.

- Floating point number, since an average is likely to have a fractional part.

Key Points

Every value has a type.

Use the built-in function

typeto find the type of a value.Types control what operations can be done on values.

Strings can be added.

Strings have a length.

Must convert numbers to strings or vice versa when operating on them.

Can mix integers and floats freely in operations.

Variables only change value when something is assigned to them.

Built-in Functions and Help

Overview

Teaching: 12 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How can I use built-in functions?

How can I find out what they do?

What kind of errors can occur in programs?

Objectives

Explain the purpose of functions.

Correctly call built-in Python functions.

Correctly nest calls to built-in functions.

Use help to display documentation for built-in functions.

Correctly describe situations in which SyntaxError and NameError occur.

Use comments to add documentation to programs.

# This sentence isn't executed by Python.

adjustment = 0.5 # Neither is this - anything after '#' is ignored.

A function may take zero or more arguments.

- We have seen some functions already — now let’s take a closer look.

- An argument is a value passed into a function.

lentakes exactly one.int,str, andfloatcreate a new value from an existing one.printtakes zero or more.printwith no arguments prints a blank line.- Must always use parentheses, even if they’re empty, so that Python knows a function is being called.

print('before')

print()

print('after')

before

after

Every function returns something.

- Every function call produces some result.

- If the function doesn’t have a useful result to return,

it usually returns the special value

None.Noneis a Python object that stands in anytime there is no value.

Commonly-used built-in functions include max, min, and round.

- Use

maxto find the largest value of one or more values. - Use

minto find the smallest. - Both work on character strings as well as numbers.

- “Larger” and “smaller” use (0-9, A-Z, a-z) to compare letters.

print(max(1, 2, 3))

print(min('a', 'A', '0'))

3

0

Functions may only work for certain (combinations of) arguments.

maxandminmust be given at least one argument.- “Largest of the empty set” is a meaningless question.

- And they must be given things that can meaningfully be compared.

print(max(1, 'a'))

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-52-3f049acf3762> in <module>

----> 1 print(max(1, 'a'))

TypeError: '>' not supported between instances of 'str' and 'int'

Functions may have default values for some arguments.

roundwill round off a floating-point number.- By default, rounds to zero decimal places.

round(3.712)

4

- We can specify the number of decimal places we want.

round(3.712, 1)

3.7

Functions attached to objects are called methods

- Functions take another form that will be common in the pandas episodes.

- Methods have parentheses like functions, but come after the variable.

- Some methods are used for internal Python operations, and are marked with double underlines.

my_string = 'Hello world!' # creation of a string object

print(len(my_string)) # the len function takes a string as an argument and returns the length of the string

print(my_string.swapcase()) # calling the swapcase method on the my_string object

print(my_string.__len__()) # calling the internal __len__ method on the my_string object, used by len(my_string)

12

hELLO WORLD!

12

- You might even see them chained together. They operate left to right.

print(my_string.isupper()) # Not all the letters are uppercase

print(my_string.upper()) # This capitalizes all the letters

print(my_string.upper().isupper()) # Now all the letters are uppercase

False

HELLO WORLD

True

Use the built-in function help to get help for a function.

- Every built-in function has online documentation.

help(round)

Help on built-in function round in module builtins:

round(number, ndigits=None)

Round a number to a given precision in decimal digits.

The return value is an integer if ndigits is omitted or None. Otherwise

the return value has the same type as the number. ndigits may be negative.

The Jupyter Notebook has two ways to get help.

- Option 1: Place the cursor near where the function is invoked in a cell

(i.e., the function name or its parameters),

- Hold down Shift, and press Tab.

- Do this several times to expand the information returned.

- Option 2: Type the function name in a cell with a question mark after it. Then run the cell.

Python reports a syntax error when it can’t understand the source of a program.

- Won’t even try to run the program if it can’t be parsed.

# Forgot to close the quote marks around the string.

name = 'Feng

File "<ipython-input-56-f42768451d55>", line 2

name = 'Feng

^

SyntaxError: EOL while scanning string literal

# An extra '=' in the assignment.

age = = 52

File "<ipython-input-57-ccc3df3cf902>", line 2

age = = 52

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

- Look more closely at the error message:

print("hello world"

File "<ipython-input-6-d1cc229bf815>", line 1

print ("hello world"

^

SyntaxError: unexpected EOF while parsing

- The message indicates a problem on first line of the input (“line 1”).

- In this case the “ipython-input” section of the file name tells us that we are working with input into IPython, the Python interpreter used by the Jupyter Notebook.

- The

-6-part of the filename indicates that the error occurred in cell 6 of our Notebook. - Next is the problematic line of code,

indicating the problem with a

^pointer.

Python reports a runtime error when something goes wrong while a program is executing.

age = 53

remaining = 100 - aege # mis-spelled 'age'

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-59-1214fb6c55fc> in <module>

1 age = 53

----> 2 remaining = 100 - aege # mis-spelled 'age'

NameError: name 'aege' is not defined

- Fix syntax errors by reading the source and runtime errors by tracing execution.

Explore the Python docs!

The official Python documentation is arguably the most complete source of information about the language. It is available in different languages and contains a lot of useful resources. The Built-in Functions page contains a catalogue of all of these functions, including the ones that we’ve covered in this lesson. Some of these are more advanced and unnecessary at the moment, but others are very simple and useful.

Key Points

Use comments to add documentation to programs.

A function may take zero or more arguments.

Commonly-used built-in functions include

max,min, andround.Functions may only work for certain (combinations of) arguments.

Functions may have default values for some arguments.

Use the built-in function

helpto get help for a function.The Jupyter Notebook has two ways to get help.

Every function returns something.

Python reports a syntax error when it can’t understand the source of a program.

Python reports a runtime error when something goes wrong while a program is executing.

Fix syntax errors by reading the source code, and runtime errors by tracing the program’s execution.

Libraries

Overview

Teaching: 6 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

How can I use software that other people have written?

How can I find out what that software does?

Objectives

Explain what software libraries are and why programmers create and use them.

Write programs that import and use modules from Python’s standard library.

Find and read documentation for the standard library interactively (in the interpreter) and online.

Most of the power of a programming language is in its libraries.

- A library is a collection of files (called modules) that contains

functions for use by other programs.

- May also contain data values (e.g., numerical constants) and other things.

- Library’s contents are supposed to be related, but there’s no way to enforce that.

- The Python standard library is an extensive suite of modules that comes with Python itself.

- Many additional libraries are available from PyPI (the Python Package Index).

Libraries and modules

A library is a collection of modules, but the terms are often used interchangeably, especially since many libraries only consist of a single module, so don’t worry if you mix them.

A program must import a library module before using it.

- Use

importto load a library module into a program’s memory. - Then refer to things from the module as

module_name.thing_name.- Python uses

.to mean “part of”.

- Python uses

- Using

math, one of the modules in the standard library:

import math

print('pi is', math.pi)

print('cos(pi) is', math.cos(math.pi))

pi is 3.141592653589793

cos(pi) is -1.0

- Have to refer to each item with the module’s name.

math.cos(pi)won’t work: the reference topidoesn’t somehow “inherit” the function’s reference tomath.

Use help to learn about the contents of a library module.

- Works just like help for a function.

help(math)

Help on module math:

NAME

math

MODULE REFERENCE

http://docs.python.org/3/library/math

The following documentation is automatically generated from the Python

source files. It may be incomplete, incorrect or include features that

are considered implementation detail and may vary between Python

implementations. When in doubt, consult the module reference at the

location listed above.

DESCRIPTION

This module is always available. It provides access to the

mathematical functions defined by the C standard.

FUNCTIONS

acos(x, /)

Return the arc cosine (measured in radians) of x.

⋮ ⋮ ⋮

Import specific items from a library module to shorten programs.

- Use

from ... import ...to load only specific items from a library module. - Then refer to them directly without library name as prefix.

from math import cos, pi

print('cos(pi) is', cos(pi))

cos(pi) is -1.0

Create an alias for a library module when importing it to shorten programs.

- Use

import ... as ...to give a library a short alias while importing it. - Then refer to items in the library using that shortened name.

import math as m

print('cos(pi) is', m.cos(m.pi))

cos(pi) is -1.0

- Commonly used for libraries that are frequently used or have long names.

- E.g., the

matplotlibplotting library is often aliased asmpl.

- E.g., the

- But can make programs harder to understand, since readers must learn your program’s aliases.

When Is Help Available?

When a colleague of yours types

help(math), Python reports an error:NameError: name 'math' is not definedWhat has your colleague forgotten to do?

Solution

Importing the math module (

import math)

Importing Specific Items

- Fill in the blanks so that the program below prints

90.0.- Do you find this version easier to read than preceding ones?

- Why wouldn’t programmers always use this form of

import?____ math import ____, ____ angle = degrees(pi / 2) print(angle)Solution

from math import degrees, pi angle = degrees(pi / 2) print(angle)Most likely you find this version easier to read since it’s less dense. The main reason not to use this form of import is to avoid name clashes. For instance, you wouldn’t import

degreesthis way if you also wanted to use the namedegreesfor a variable or function of your own. Or if you were to also import a function nameddegreesfrom another library.

Key Points

Most of the power of a programming language is in its libraries.

A program must import a library module in order to use it.

Use

helpto learn about the contents of a library module.Import specific items from a library to shorten programs.

Create an alias for a library when importing it to shorten programs.

Reading Tabular Data into DataFrames

Overview

Teaching: 8 min

Exercises: 7 minQuestions

How can I read tabular data?

Objectives

Import the Pandas library.

Use Pandas to load a simple CSV data set.

Get some basic information about a Pandas DataFrame.

Use the Pandas library to do statistics on tabular data.

- Pandas is a widely-used Python library for statistics, particularly on tabular data.

- Load it with

import pandas as pd. The alias pd is commonly used for Pandas. - Read a Comma Separated Values (CSV) data file with

pd.read_csv.- Argument is the name of the file to be read.

- Assign result to a variable to store the data that was read.

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_oceania.csv')

print(data)

country gdpPercap_1952 gdpPercap_1957 gdpPercap_1962 \

0 Australia 10039.59564 10949.64959 12217.22686

1 New Zealand 10556.57566 12247.39532 13175.67800

gdpPercap_1967 gdpPercap_1972 gdpPercap_1977 gdpPercap_1982 \

0 14526.12465 16788.62948 18334.19751 19477.00928

1 14463.91893 16046.03728 16233.71770 17632.41040

gdpPercap_1987 gdpPercap_1992 gdpPercap_1997 gdpPercap_2002 \

0 21888.88903 23424.76683 26997.93657 30687.75473

1 19007.19129 18363.32494 21050.41377 23189.80135

gdpPercap_2007

0 34435.36744

1 25185.00911

- The columns in a dataframe are the observed variables, and the rows are the observations.

- Pandas uses backslash

\to show wrapped lines when output is too wide to fit the screen.

File Not Found

Our lessons store their data files in a

datasub-directory, which is why the path to the file isdata/gapminder_gdp_oceania.csv. If you forget to includedata/, or if you include it but your copy of the file is somewhere else, you will get a runtime error that ends with a line like this:FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'data/gapminder_gdp_oceania.csv'

Use index_col to specify that a column’s values should be used as row headings.

- Row headings are numbers (0 and 1 in this case).

- Really want to index by country.

- Pass the name of the column to

read_csvas itsindex_colparameter to do this.

data = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_oceania.csv', index_col='country')

print(data)

gdpPercap_1952 gdpPercap_1957 gdpPercap_1962 gdpPercap_1967 \

country

Australia 10039.59564 10949.64959 12217.22686 14526.12465

New Zealand 10556.57566 12247.39532 13175.67800 14463.91893

gdpPercap_1972 gdpPercap_1977 gdpPercap_1982 gdpPercap_1987 \

country

Australia 16788.62948 18334.19751 19477.00928 21888.88903

New Zealand 16046.03728 16233.71770 17632.41040 19007.19129

gdpPercap_1992 gdpPercap_1997 gdpPercap_2002 gdpPercap_2007

country

Australia 23424.76683 26997.93657 30687.75473 34435.36744

New Zealand 18363.32494 21050.41377 23189.80135 25185.00911

Use the DataFrame.info() method to find out more about a dataframe.

data.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 2 entries, Australia to New Zealand

Data columns (total 12 columns):

gdpPercap_1952 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_1957 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_1962 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_1967 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_1972 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_1977 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_1982 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_1987 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_1992 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_1997 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_2002 2 non-null float64

gdpPercap_2007 2 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(12)

memory usage: 208.0+ bytes

- This is a

DataFrame - Two rows named

'Australia'and'New Zealand' - Twelve columns, each of which has two actual 64-bit floating point values.

- We will talk later about null values, which are used to represent missing observations.

- Uses 208 bytes of memory.

The DataFrame.columns variable stores information about the dataframe’s columns.

- Note that this is data, not a method. (It doesn’t have parentheses.)

- Like

math.pi. - So do not use

()to try to call it.

- Like

- Called a member variable, or just member.

print(data.columns)

Index(['gdpPercap_1952', 'gdpPercap_1957', 'gdpPercap_1962', 'gdpPercap_1967',

'gdpPercap_1972', 'gdpPercap_1977', 'gdpPercap_1982', 'gdpPercap_1987',

'gdpPercap_1992', 'gdpPercap_1997', 'gdpPercap_2002', 'gdpPercap_2007'],

dtype='object')

Use DataFrame.T to transpose a dataframe.

- Sometimes want to treat columns as rows and vice versa.

- Transpose (written

.T) doesn’t copy the data, just changes the program’s view of it. - Like

columns, it is a member variable.

print(data.T)

country Australia New Zealand

gdpPercap_1952 10039.59564 10556.57566

gdpPercap_1957 10949.64959 12247.39532

gdpPercap_1962 12217.22686 13175.67800

gdpPercap_1967 14526.12465 14463.91893

gdpPercap_1972 16788.62948 16046.03728

gdpPercap_1977 18334.19751 16233.71770

gdpPercap_1982 19477.00928 17632.41040

gdpPercap_1987 21888.88903 19007.19129

gdpPercap_1992 23424.76683 18363.32494

gdpPercap_1997 26997.93657 21050.41377

gdpPercap_2002 30687.75473 23189.80135

gdpPercap_2007 34435.36744 25185.00911

Use DataFrame.describe() to get summary statistics about data.

DataFrame.describe() gets the summary statistics of the columns.

print(data.describe())

gdpPercap_1952 gdpPercap_1957 gdpPercap_1962 gdpPercap_1967 \

count 2.000000 2.000000 2.000000 2.000000

mean 10298.085650 11598.522455 12696.452430 14495.021790

std 365.560078 917.644806 677.727301 43.986086

min 10039.595640 10949.649590 12217.226860 14463.918930

25% 10168.840645 11274.086022 12456.839645 14479.470360

50% 10298.085650 11598.522455 12696.452430 14495.021790

75% 10427.330655 11922.958888 12936.065215 14510.573220

max 10556.575660 12247.395320 13175.678000 14526.124650

gdpPercap_1972 gdpPercap_1977 gdpPercap_1982 gdpPercap_1987 \

count 2.00000 2.000000 2.000000 2.000000

mean 16417.33338 17283.957605 18554.709840 20448.040160

std 525.09198 1485.263517 1304.328377 2037.668013

min 16046.03728 16233.717700 17632.410400 19007.191290

25% 16231.68533 16758.837652 18093.560120 19727.615725

50% 16417.33338 17283.957605 18554.709840 20448.040160

75% 16602.98143 17809.077557 19015.859560 21168.464595

max 16788.62948 18334.197510 19477.009280 21888.889030

gdpPercap_1992 gdpPercap_1997 gdpPercap_2002 gdpPercap_2007

count 2.000000 2.000000 2.000000 2.000000

mean 20894.045885 24024.175170 26938.778040 29810.188275

std 3578.979883 4205.533703 5301.853680 6540.991104

min 18363.324940 21050.413770 23189.801350 25185.009110

25% 19628.685413 22537.294470 25064.289695 27497.598692

50% 20894.045885 24024.175170 26938.778040 29810.188275

75% 22159.406358 25511.055870 28813.266385 32122.777857

max 23424.766830 26997.936570 30687.754730 34435.367440

- Not particularly useful with just two records, but very helpful when there are thousands.

Reading Other Data

Read the data in

gapminder_gdp_americas.csv(which should be in the same directory asgapminder_gdp_oceania.csv) into a variable calledamericasand display its summary statistics.Solution

To read in a CSV, we use

pd.read_csvand pass the filename'data/gapminder_gdp_americas.csv'to it. We also once again pass the column name'country'to the parameterindex_colin order to index by country. The summary statistics can be displayed with theDataFrame.describe()method.americas = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_americas.csv', index_col='country') americas.describe()

Reading Files in Other Directories

The data for your current project is stored in a file called

microbes.csv, which is located in a folder calledfield_data. You are doing analysis in a notebook calledanalysis.ipynbin a sibling folder calledthesis:your_home_directory +-- field_data/ | +-- microbes.csv +-- thesis/ +-- analysis.ipynbWhat value(s) should you pass to

read_csvto readmicrobes.csvinanalysis.ipynb?Solution

We need to specify the path to the file of interest in the call to

pd.read_csv. We first need to ‘jump’ out of the folderthesisusing ‘../’ and then into the folderfield_datausing ‘field_data/’. Then we can specify the filename `microbes.csv. The result is as follows:data_microbes = pd.read_csv('../field_data/microbes.csv')

Writing Data

As well as the

read_csvfunction for reading data from a file, Pandas provides ato_csvfunction to write dataframes to files. Applying what you’ve learned about reading from files, write one of your dataframes to a file calledprocessed.csv. You can usehelpto get information on how to useto_csv.Solution

In order to write the DataFrame

americasto a file calledprocessed.csv, execute the following command:americas.to_csv('processed.csv')For help on

to_csv, you could execute, for example:help(americas.to_csv)Note that

help(to_csv)throws an error! This is a subtlety and is due to the fact thatto_csvis NOT a function in and of itself and the actual call isamericas.to_csv.

Key Points

Use the Pandas library to get basic statistics out of tabular data.

Use

index_colto specify that a column’s values should be used as row headings.Use

DataFrame.infoto find out more about a dataframe.The

DataFrame.columnsvariable stores information about the dataframe’s columns.Use

DataFrame.Tto transpose a dataframe.Use

DataFrame.describeto get summary statistics about data.

Pandas DataFrames

Overview

Teaching: 12 min

Exercises: 13 minQuestions

How can I do statistical analysis of tabular data?

Objectives

Select individual values from a Pandas dataframe.

Select entire rows or entire columns from a dataframe.

Select a subset of both rows and columns from a dataframe in a single operation.

Select a subset of a dataframe by a single Boolean criterion.

Selecting values

To access a value at the position [i,j] of a DataFrame, we have two options, depending on

what is the meaning of i in use.

Remember that a DataFrame provides an index as a way to identify the rows of the table;

a row, then, has a position inside the table as well as a label, which

uniquely identifies its entry in the DataFrame.

Use DataFrame.iloc[..., ...] to select values by their (entry) position

- Can specify location by numerical index analogously to 2D version of character selection in strings.

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv', index_col='country')

print(data.iloc[0, 0])

1601.056136

Use DataFrame.loc[..., ...] to select values by their (entry) label.

- Can specify location by row name analogously to 2D version of dictionary keys.

print(data.loc["Albania", "gdpPercap_1952"])

1601.056136

Use : on its own to mean all columns or all rows.

- Just like Python’s usual slicing notation.

print(data.loc["Albania", :])

gdpPercap_1952 1601.056136

gdpPercap_1957 1942.284244

gdpPercap_1962 2312.888958

gdpPercap_1967 2760.196931

gdpPercap_1972 3313.422188

gdpPercap_1977 3533.003910

gdpPercap_1982 3630.880722

gdpPercap_1987 3738.932735

gdpPercap_1992 2497.437901

gdpPercap_1997 3193.054604

gdpPercap_2002 4604.211737

gdpPercap_2007 5937.029526

Name: Albania, dtype: float64

- Would get the same result printing

data.loc["Albania"](without a second index).

print(data.loc[:, "gdpPercap_1952"])

country

Albania 1601.056136

Austria 6137.076492

Belgium 8343.105127

⋮ ⋮ ⋮

Switzerland 14734.232750

Turkey 1969.100980

United Kingdom 9979.508487

Name: gdpPercap_1952, dtype: float64

- Would get the same result printing

data["gdpPercap_1952"]

Select multiple columns or rows using DataFrame.loc and a named slice.

print(data.loc['Italy':'Poland', 'gdpPercap_1962':'gdpPercap_1972'])

gdpPercap_1962 gdpPercap_1967 gdpPercap_1972

country

Italy 8243.582340 10022.401310 12269.273780

Montenegro 4649.593785 5907.850937 7778.414017

Netherlands 12790.849560 15363.251360 18794.745670

Norway 13450.401510 16361.876470 18965.055510

Poland 5338.752143 6557.152776 8006.506993

In the above code, we discover that slicing using loc is inclusive at both

ends, which differs from slicing using iloc, where slicing indicates

everything up to but not including the final index.

Result of slicing can be used in further operations.

- Usually don’t just print a slice.

- All the statistical operators that work on entire dataframes work the same way on slices.

- E.g., calculate max of a slice.

print(data.loc['Italy':'Poland', 'gdpPercap_1962':'gdpPercap_1972'].max())

gdpPercap_1962 13450.40151

gdpPercap_1967 16361.87647

gdpPercap_1972 18965.05551

dtype: float64

print(data.loc['Italy':'Poland', 'gdpPercap_1962':'gdpPercap_1972'].min())

gdpPercap_1962 4649.593785

gdpPercap_1967 5907.850937

gdpPercap_1972 7778.414017

dtype: float64

Use comparisons to select data based on value.

- Comparison is applied element by element.

- Returns a similarly-shaped dataframe of

TrueandFalse.

# Use a subset of data to keep output readable.

subset = data.loc['Italy':'Poland', 'gdpPercap_1962':'gdpPercap_1972']

print('Subset of data:\n', subset)

# Which values were greater than 10000 ?

print('\nWhere are values large?\n', subset > 10000)

Subset of data:

gdpPercap_1962 gdpPercap_1967 gdpPercap_1972

country

Italy 8243.582340 10022.401310 12269.273780

Montenegro 4649.593785 5907.850937 7778.414017

Netherlands 12790.849560 15363.251360 18794.745670

Norway 13450.401510 16361.876470 18965.055510

Poland 5338.752143 6557.152776 8006.506993

Where are values large?

gdpPercap_1962 gdpPercap_1967 gdpPercap_1972

country

Italy False True True

Montenegro False False False

Netherlands True True True

Norway True True True

Poland False False False

Select values or NaN using a Boolean mask.

- A frame full of Booleans is sometimes called a mask because of how it can be used.

mask = subset > 10000

print(subset[mask])

gdpPercap_1962 gdpPercap_1967 gdpPercap_1972

country

Italy NaN 10022.40131 12269.27378

Montenegro NaN NaN NaN

Netherlands 12790.84956 15363.25136 18794.74567

Norway 13450.40151 16361.87647 18965.05551

Poland NaN NaN NaN

- Get the value where the mask is true, and NaN (Not a Number) where it is false.

- Useful because NaNs are ignored by operations like max, min, average, etc.

print(subset[subset > 10000].describe())

gdpPercap_1962 gdpPercap_1967 gdpPercap_1972

count 2.000000 3.000000 3.000000

mean 13120.625535 13915.843047 16676.358320

std 466.373656 3408.589070 3817.597015

min 12790.849560 10022.401310 12269.273780

25% 12955.737547 12692.826335 15532.009725

50% 13120.625535 15363.251360 18794.745670

75% 13285.513523 15862.563915 18879.900590

max 13450.401510 16361.876470 18965.055510

Selection of Individual Values

Assume Pandas has been imported into your notebook and the Gapminder GDP data for Europe has been loaded:

import pandas as pd df = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv', index_col='country')Write an expression to find the Per Capita GDP of Serbia in 2007.

Solution

The selection can be done by using the labels for both the row (“Serbia”) and the column (“gdpPercap_2007”):

print(df.loc['Serbia', 'gdpPercap_2007'])The output is

9786.534714

Extent of Slicing

- Do the two statements below produce the same output?

- Based on this, what rule governs what is included (or not) in numerical slices and named slices in Pandas?

print(df.iloc[0:2, 0:2]) print(df.loc['Albania':'Belgium', 'gdpPercap_1952':'gdpPercap_1962'])Solution

No, they do not produce the same output! The output of the first statement is:

gdpPercap_1952 gdpPercap_1957 country Albania 1601.056136 1942.284244 Austria 6137.076492 8842.598030The second statement gives:

gdpPercap_1952 gdpPercap_1957 gdpPercap_1962 country Albania 1601.056136 1942.284244 2312.888958 Austria 6137.076492 8842.598030 10750.721110 Belgium 8343.105127 9714.960623 10991.206760Clearly, the second statement produces an additional column and an additional row compared to the first statement.

What conclusion can we draw? We see that a numerical slice, 0:2, omits the final index (i.e. index 2) in the range provided, while a named slice, ‘gdpPercap_1952’:’gdpPercap_1962’, includes the final element.

Practice with Selection

Assume Pandas has been imported and the Gapminder GDP data for Europe has been loaded. Write an expression to select each of the following:

- GDP per capita for each country in 1982.

- GDP per capita for Denmark for each year.

- GDP per capita for each country in 2007 as a ratio to the GDP per capita for that country in 1952.

Solution

1:

data['gdpPercap_1982']2:

data.loc['Denmark',:]3:

data['gdpPercap_2007']/data['gdpPercap_1952']

Exploring available methods using the

dir()functionPython includes a

dir()function that can be used to display all of the available methods (functions) that are built into a data object. In Episode 4, we used some methods with a string. But we can see many more are available by usingdir():my_string = 'Hello world!' # creation of a string object dir(my_string)This command returns:

['__add__', ... '__subclasshook__', 'capitalize', 'casefold', 'center', ... 'upper', 'zfill']You can use

help()or Shift+Tab to get more information about what these methods do.Assume Pandas has been imported and the Gapminder GDP data for Europe has been loaded as

data. Then, usedir()to find the function that prints out the median per-capita GDP across all European countries for each year that information is available.Solution

Among many choices,

dir()lists themedian()function as a possibility. Thus,data.median()

Key Points

Use

DataFrame.iloc[..., ...]to select values by integer location.Use

:on its own to mean all columns or all rows.Select multiple columns or rows using

DataFrame.locand a named slice.Result of slicing can be used in further operations.

Use comparisons to select data based on value.

Select values or NaN using a Boolean mask.

Break

Overview

Teaching: 0 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

Objectives

Reflection exercise

Reflect on and discuss the following:

- What are the different kinds of errors Python will report?

- Did the code always produce the results you expected? If not, why?

- Is there something we can do to prevent errors when we write code?

Key Points

Plotting

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

How can I plot my data?

How can I save my plot for publishing?

Objectives

Create a time series plot showing a single data set.

Create a scatter plot showing relationship between two data sets.

matplotlib is the most widely used scientific plotting library in Python.

- Commonly use a sub-library called

matplotlib.pyplot. - The Jupyter Notebook will render plots inline by default.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

- Simple plots are then (fairly) simple to create.

time = [0, 1, 2, 3]

position = [0, 100, 200, 300]

plt.plot(time, position)

plt.xlabel('Time (hr)')

plt.ylabel('Position (km)')

Display All Open Figures

In our Jupyter Notebook example, running the cell should generate the figure directly below the code. The figure is also included in the Notebook document for future viewing. However, other Python environments like an interactive Python session started from a terminal or a Python script executed via the command line require an additional command to display the figure.

Instruct

matplotlibto show a figure:plt.show()This command can also be used within a Notebook - for instance, to display multiple figures if several are created by a single cell.

Plot data directly from a Pandas dataframe.

- We can also plot Pandas dataframes.

- This implicitly uses

matplotlib.pyplot. - Before plotting, we convert the column headings from a

stringtointegerdata type, since they represent numerical values

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_oceania.csv', index_col='country')

# Extract year from last 4 characters of each column name

# The current column names are structured as 'gdpPercap_(year)',

# so we want to keep the (year) part only for clarity when plotting GDP vs. years

# To do this we use strip(), which removes from the string the characters stated in the argument

# This method works on strings, so we call str before strip()

years = data.columns.str.strip('gdpPercap_')

# Convert year values to integers, saving results back to dataframe

data.columns = years.astype(int)

data.loc['Australia'].plot()

Select and transform data, then plot it.

- By default,

DataFrame.plotplots with the rows as the X axis. - We can transpose the data in order to plot multiple series.

data.T.plot()

plt.ylabel('GDP per capita')

Many styles of plot are available.

- For example, do a bar plot using a fancier style.

plt.style.use('ggplot')

data.T.plot(kind='bar')

plt.ylabel('GDP per capita')

Data can also be plotted by calling the matplotlib plot function directly.

- The command is

plt.plot(x, y) - The color and format of markers can also be specified as an additional optional argument e.g.,

b-is a blue line,g--is a green dashed line.

Get Australia data from dataframe

years = data.columns

gdp_australia = data.loc['Australia']

plt.plot(years, gdp_australia, 'g--')

Can plot many sets of data together.

# Select two countries' worth of data.

gdp_australia = data.loc['Australia']

gdp_nz = data.loc['New Zealand']

# Plot with differently-colored markers.

plt.plot(years, gdp_australia, 'b-', label='Australia')

plt.plot(years, gdp_nz, 'g-', label='New Zealand')

# Create legend.

plt.legend(loc='upper left')

plt.xlabel('Year')

plt.ylabel('GDP per capita ($)')

Adding a Legend

Often when plotting multiple datasets on the same figure it is desirable to have a legend describing the data.

This can be done in

matplotlibin two stages:

- Provide a label for each dataset in the figure:

plt.plot(years, gdp_australia, label='Australia') plt.plot(years, gdp_nz, label='New Zealand')

- Instruct

matplotlibto create the legend.plt.legend()By default matplotlib will attempt to place the legend in a suitable position. If you would rather specify a position this can be done with the

loc=argument, e.g to place the legend in the upper left corner of the plot, specifyloc='upper left'

- Plot a scatter plot correlating the GDP of Australia and New Zealand

- Use either

plt.scatterorDataFrame.plot.scatter

plt.scatter(gdp_australia, gdp_nz)

data.T.plot.scatter(x = 'Australia', y = 'New Zealand')

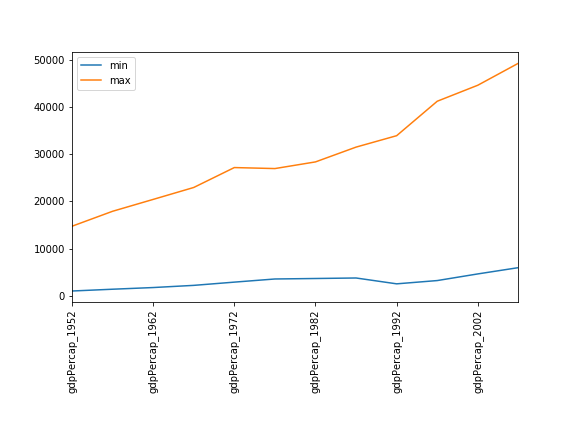

Minima and Maxima

Fill in the blanks below to plot the minimum GDP per capita over time for all the countries in Europe. Modify it again to plot the maximum GDP per capita over time for Europe.

data_europe = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv', index_col='country') data_europe.____.plot(label='min') data_europe.____ plt.legend(loc='best') plt.xticks(rotation=90)Solution

data_europe = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv', index_col='country') data_europe.min().plot(label='min') data_europe.max().plot(label='max') plt.legend(loc='best') plt.xticks(rotation=90)

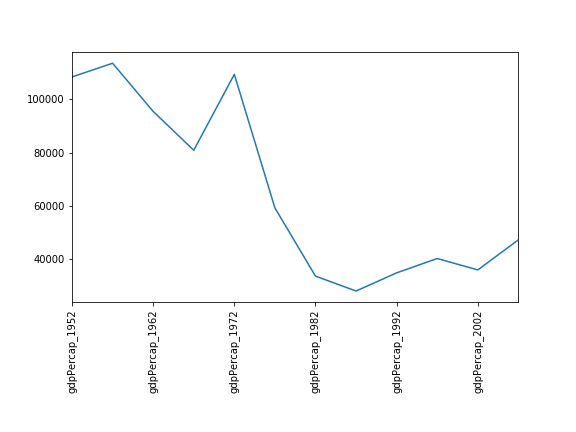

Correlations

Modify the example in the notes to create a scatter plot showing the relationship between the minimum and maximum GDP per capita among the countries in Asia for each year in the data set. What relationship do you see (if any)?

Solution

data_asia = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_asia.csv', index_col='country') data_asia.describe().T.plot(kind='scatter', x='min', y='max')

No particular correlations can be seen between the minimum and maximum gdp values year on year. It seems the fortunes of asian countries do not rise and fall together.

You might note that the variability in the maximum is much higher than that of the minimum. Take a look at the maximum and the max indexes:

data_asia = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_gdp_asia.csv', index_col='country') data_asia.max().plot() print(data_asia.idxmax()) print(data_asia.idxmin())Solution

Seems the variability in this value is due to a sharp drop after 1972. Some geopolitics at play perhaps? Given the dominance of oil producing countries, maybe the Brent crude index would make an interesting comparison? Whilst Myanmar consistently has the lowest gdp, the highest gdb nation has varied more notably.

More Correlations

This short program creates a plot showing the correlation between GDP and life expectancy for 2007, normalizing marker size by population:

data_all = pd.read_csv('data/gapminder_all.csv', index_col='country') data_all.plot(kind='scatter', x='gdpPercap_2007', y='lifeExp_2007', s=data_all['pop_2007']/1e6)Using online help and other resources, explain what each argument to

plotdoes.Solution

A good place to look is the documentation for the plot function - help(data_all.plot).

kind - As seen already this determines the kind of plot to be drawn.

x and y - A column name or index that determines what data will be placed on the x and y axes of the plot

s - Details for this can be found in the documentation of plt.scatter. A single number or one value for each data point. Determines the size of the plotted points.

Saving your plot to a file

If you are satisfied with the plot you see you may want to save it to a file, perhaps to include it in a publication. There is a function in the matplotlib.pyplot module that accomplishes this: savefig. Calling this function, e.g. with

plt.savefig('my_figure.png')will save the current figure to the file

my_figure.png. The file format will automatically be deduced from the file name extension (other formats are pdf, ps, eps and svg).Note that functions in

pltrefer to a global figure variable and after a figure has been displayed to the screen (e.g. withplt.show) matplotlib will make this variable refer to a new empty figure. Therefore, make sure you callplt.savefigbefore the plot is displayed to the screen, otherwise you may find a file with an empty plot.When using dataframes, data is often generated and plotted to screen in one line, and

plt.savefigseems not to be a possible approach. One possibility to save the figure to file is then to

- save a reference to the current figure in a local variable (with

plt.gcf)- call the

savefigclass method from that variable.fig = plt.gcf() # get current figure data.plot(kind='bar') fig.savefig('my_figure.png')

Making your plots accessible

Whenever you are generating plots to go into a paper or a presentation, there are a few things you can do to make sure that everyone can understand your plots.

- Always make sure your text is large enough to read. Use the

fontsizeparameter inxlabel,ylabel,title, andlegend, andtick_paramswithlabelsizeto increase the text size of the numbers on your axes.- Similarly, you should make your graph elements easy to see. Use

sto increase the size of your scatterplot markers andlinewidthto increase the sizes of your plot lines.- Using color (and nothing else) to distinguish between different plot elements will make your plots unreadable to anyone who is colorblind, or who happens to have a black-and-white office printer. For lines, the

linestyleparameter lets you use different types of lines. For scatterplots,markerlets you change the shape of your points. If you’re unsure about your colors, you can use Coblis or Color Oracle to simulate what your plots would look like to those with colorblindness.

Key Points

matplotlibis the most widely used scientific plotting library in Python.Plot data directly from a Pandas dataframe.

Select and transform data, then plot it.

Many styles of plot are available: see the Python Graph Gallery for more options.

Can plot many sets of data together.

Lists

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How can I store multiple values?

Objectives

Explain why programs need collections of values.

Write programs that create flat lists, index them, slice them, and modify them through assignment and method calls.

A list stores many values in a single structure.

- Doing calculations with a hundred variables called

pressure_001,pressure_002, etc., would be at least as slow as doing them by hand. - Use a list to store many values together.

- Contained within square brackets

[...]. - Values separated by commas

,.

- Contained within square brackets

- Use

lento find out how many values are in a list.

pressures = [0.273, 0.275, 0.277, 0.275, 0.276]

print('pressures:', pressures)

print('length:', len(pressures))

pressures: [0.273, 0.275, 0.277, 0.275, 0.276]

length: 5

Use an item’s index to fetch it from a list.

- Just like strings.

print('zeroth item of pressures:', pressures[0])

print('fourth item of pressures:', pressures[4])

zeroth item of pressures: 0.273

fourth item of pressures: 0.276

Lists’ values can be replaced by assigning to them.

- Use an index expression on the left of assignment to replace a value.

pressures[0] = 0.265

print('pressures is now:', pressures)

pressures is now: [0.265, 0.275, 0.277, 0.275, 0.276]

Appending items to a list lengthens it.

- Use

list_name.appendto add items to the end of a list.

primes = [2, 3, 5]

print('primes is initially:', primes)

primes.append(7)

print('primes has become:', primes)

primes is initially: [2, 3, 5]

primes has become: [2, 3, 5, 7]

appendis a method of lists.- Like a function, but tied to a particular object.

- Use

object_name.method_nameto call methods.- Deliberately resembles the way we refer to things in a library.

- We will meet other methods of lists as we go along.

- Use

help(list)for a preview.

- Use

extendis similar toappend, but it allows you to combine two lists. For example:

teen_primes = [11, 13, 17, 19]

middle_aged_primes = [37, 41, 43, 47]

print('primes is currently:', primes)

primes.extend(teen_primes)

print('primes has now become:', primes)

primes.append(middle_aged_primes)

print('primes has finally become:', primes)

primes is currently: [2, 3, 5, 7]

primes has now become: [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19]

primes has finally become: [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, [37, 41, 43, 47]]

Note that while extend maintains the “flat” structure of the list, appending a list to a list makes the result

two-dimensional - the last element in primes is a list, not an integer.

Use del to remove items from a list entirely.

- We use

del list_name[index]to remove an element from a list (in the example, 9 is not a prime number) and thus shorten it. delis not a function or a method, but a statement in the language.

primes = [2, 3, 5, 7, 9]

print('primes before removing last item:', primes)

del primes[4]

print('primes after removing last item:', primes)

primes before removing last item: [2, 3, 5, 7, 9]

primes after removing last item: [2, 3, 5, 7]

The empty list contains no values.

- Use

[]on its own to represent a list that doesn’t contain any values.- “The zero of lists.”

- Helpful as a starting point for collecting values (which we will see in the next episode).

Lists may contain values of different types.

- A single list may contain numbers, strings, and anything else.

goals = [1, 'Create lists.', 2, 'Extract items from lists.', 3, 'Modify lists.']

Character strings can be indexed like lists.

- Get single characters from a character string using indexes in square brackets.

element = 'carbon'

print('zeroth character:', element[0])

print('third character:', element[3])

zeroth character: c

third character: b

Character strings are immutable.

- Cannot change the characters in a string after it has been created.

- Immutable: can’t be changed after creation.

- In contrast, lists are mutable: they can be modified in place.

- Python considers the string to be a single value with parts, not a collection of values.

element[0] = 'C'

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

- Lists and character strings are both collections.

Indexing beyond the end of the collection is an error.

- Python reports an

IndexErrorif we attempt to access a value that doesn’t exist.- This is a kind of runtime error.

- Cannot be detected as the code is parsed because the index might be calculated based on data.

print('99th element of element is:', element[99])

IndexError: string index out of range

Fill in the Blanks

Fill in the blanks so that the program below produces the output shown.

values = ____ values.____(1) values.____(3) values.____(5) print('first time:', values) values = values[____] print('second time:', values)first time: [1, 3, 5] second time: [3, 5]Solution

values = [] values.append(1) values.append(3) values.append(5) print('first time:', values) values = values[1:] print('second time:', values)

How Large is a Slice?

If ‘low’ and ‘high’ are both non-negative integers, how long is the list

values[low:high]?Solution

The list

values[low:high]hashigh - lowelements. For example,values[1:4]has the 3 elementsvalues[1],values[2], andvalues[3]. Note that the expression will only work ifhighis less than the total length of the listvalues.

From Strings to Lists and Back

Given this:

print('string to list:', list('tin')) print('list to string:', ''.join(['g', 'o', 'l', 'd']))string to list: ['t', 'i', 'n'] list to string: gold

- What does

list('some string')do?- What does

'-'.join(['x', 'y', 'z'])generate?Solution

list('some string')converts a string into a list containing all of its characters.joinreturns a string that is the concatenation of each string element in the list and adds the separator between each element in the list. This results inx-y-z. The separator between the elements is the string that provides this method.

Working With the End

What does the following program print?

element = 'helium' print(element[-1])

- How does Python interpret a negative index?

- If a list or string has N elements, what is the most negative index that can safely be used with it, and what location does that index represent?

- If

valuesis a list, what doesdel values[-1]do?- How can you display all elements but the last one without changing

values? (Hint: you will need to combine slicing and negative indexing.)Solution

The program prints

m.

- Python interprets a negative index as starting from the end (as opposed to starting from the beginning). The last element is

-1.- The last index that can safely be used with a list of N elements is element

-N, which represents the first element.del values[-1]removes the last element from the list.values[:-1]

Stepping Through a List

What does the following program print?

element = 'fluorine' print(element[::2]) print(element[::-1])

- If we write a slice as

low:high:stride, what doesstridedo?- What expression would select all of the even-numbered items from a collection?

Solution

The program prints

furn eniroulf

strideis the step size of the slice.- The slice

1::2selects all even-numbered items from a collection: it starts with element1(which is the second element, since indexing starts at0), goes on until the end (since noendis given), and uses a step size of2(i.e., selects every second element).

Slice Bounds

What does the following program print?

element = 'lithium' print(element[0:20]) print(element[-1:3])Solution

lithiumThe first statement prints the whole string, since the slice goes beyond the total length of the string. The second statement returns an empty string, because the slice goes “out of bounds” of the string.

Sort and Sorted

What do these two programs print? In simple terms, explain the difference between

sorted(letters)andletters.sort().# Program A letters = list('gold') result = sorted(letters) print('letters is', letters, 'and result is', result)# Program B letters = list('gold') result = letters.sort() print('letters is', letters, 'and result is', result)Solution

Program A prints

letters is ['g', 'o', 'l', 'd'] and result is ['d', 'g', 'l', 'o']Program B prints

letters is ['d', 'g', 'l', 'o'] and result is None

sorted(letters)returns a sorted copy of the listletters(the original listlettersremains unchanged), whileletters.sort()sorts the listlettersin-place and does not return anything.

Copying (or Not)

What do these two programs print? In simple terms, explain the difference between

new = oldandnew = old[:].# Program A old = list('gold') new = old # simple assignment new[0] = 'D' print('new is', new, 'and old is', old)# Program B old = list('gold') new = old[:] # assigning a slice new[0] = 'D' print('new is', new, 'and old is', old)Solution

Program A prints

new is ['D', 'o', 'l', 'd'] and old is ['D', 'o', 'l', 'd']Program B prints

new is ['D', 'o', 'l', 'd'] and old is ['g', 'o', 'l', 'd']

new = oldmakesnewa reference to the listold;newandoldpoint towards the same object.

new = old[:]however creates a new list objectnewcontaining all elements from the listold;newandoldare different objects.

Key Points

A list stores many values in a single structure.

Use an item’s index to fetch it from a list.

Lists’ values can be replaced by assigning to them.

Appending items to a list lengthens it.

Use

delto remove items from a list entirely.The empty list contains no values.

Lists may contain values of different types.

Character strings can be indexed like lists.

Character strings are immutable.

Indexing beyond the end of the collection is an error.

For Loops

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

How can I make a program do many things?

Objectives

Explain what for loops are normally used for.

Trace the execution of a simple (unnested) loop and correctly state the values of variables in each iteration.

Write for loops that use the Accumulator pattern to aggregate values.

A for loop executes commands once for each value in a collection.

- Doing calculations on the values in a list one by one

is as painful as working with

pressure_001,pressure_002, etc. - A for loop tells Python to execute some statements once for each value in a list, a character string, or some other collection.

- “for each thing in this group, do these operations”

for number in [2, 3, 5]:

print(number)

- This

forloop is equivalent to:

print(2)

print(3)

print(5)

- And the

forloop’s output is:

2

3

5

A for loop is made up of a collection, a loop variable, and a body.

for number in [2, 3, 5]:

print(number)

- The collection,

[2, 3, 5], is what the loop is being run on. - The body,

print(number), specifies what to do for each value in the collection. - The loop variable,

number, is what changes for each iteration of the loop.- The “current thing”.

The first line of the for loop must end with a colon, and the body must be indented.

- The colon at the end of the first line signals the start of a block of statements.

- Python uses indentation rather than

{}orbegin/endto show nesting.- Any consistent indentation is legal, but almost everyone uses four spaces.

for number in [2, 3, 5]:

print(number)

IndentationError: expected an indented block

- Indentation is always meaningful in Python.

firstName = "Jon"

lastName = "Smith"

File "<ipython-input-7-f65f2962bf9c>", line 2

lastName = "Smith"

^

IndentationError: unexpected indent

- This error can be fixed by removing the extra spaces at the beginning of the second line.

Loop variables can be called anything.

- As with all variables, loop variables are:

- Created on demand.

- Meaningless: their names can be anything at all.

for kitten in [2, 3, 5]:

print(kitten)

The body of a loop can contain many statements.

- But no loop should be more than a few lines long.

- Hard for human beings to keep larger chunks of code in mind.

primes = [2, 3, 5]

for p in primes:

squared = p ** 2

cubed = p ** 3

print(p, squared, cubed)

2 4 8

3 9 27

5 25 125

Use range to iterate over a sequence of numbers.

- The built-in function

rangeproduces a sequence of numbers.- Not a list: the numbers are produced on demand to make looping over large ranges more efficient.

range(N)is the numbers 0..N-1- Exactly the legal indices of a list or character string of length N

print('a range is not a list: range(0, 3)')

for number in range(0, 3):

print(number)

a range is not a list: range(0, 3)

0

1

2

The Accumulator pattern turns many values into one.

- A common pattern in programs is to:

- Initialize an accumulator variable to zero, the empty string, or the empty list.

- Update the variable with values from a collection.

# Sum the first 10 integers.

total = 0

for number in range(10):

total = total + (number + 1)

print(total)

55

- Read

total = total + (number + 1)as:- Add 1 to the current value of the loop variable

number. - Add that to the current value of the accumulator variable

total. - Assign that to

total, replacing the current value.

- Add 1 to the current value of the loop variable

- We have to add

number + 1becauserangeproduces 0..9, not 1..10.

Classifying Errors

Is an indentation error a syntax error or a runtime error?

Solution

An IndentationError is a syntax error. Programs with syntax errors cannot be started. A program with a runtime error will start but an error will be thrown under certain conditions.

Tracing Execution

Create a table showing the numbers of the lines that are executed when this program runs, and the values of the variables after each line is executed.

total = 0 for char in "tin": total = total + 1Solution

Line no Variables 1 total = 0 2 total = 0 char = ‘t’ 3 total = 1 char = ‘t’ 2 total = 1 char = ‘i’ 3 total = 2 char = ‘i’ 2 total = 2 char = ‘n’ 3 total = 3 char = ‘n’

Reversing a String

Fill in the blanks in the program below so that it prints “nit” (the reverse of the original character string “tin”).

original = "tin" result = ____ for char in original: result = ____ print(result)Solution

original = "tin" result = "" for char in original: result = char + result print(result)

Practice Accumulating

Fill in the blanks in each of the programs below to produce the indicated result.

# Total length of the strings in the list: ["red", "green", "blue"] => 12 total = 0 for word in ["red", "green", "blue"]: ____ = ____ + len(word) print(total)Solution

total = 0 for word in ["red", "green", "blue"]: total = total + len(word) print(total)# List of word lengths: ["red", "green", "blue"] => [3, 5, 4] lengths = ____ for word in ["red", "green", "blue"]: lengths.____(____) print(lengths)Solution

lengths = [] for word in ["red", "green", "blue"]: lengths.append(len(word)) print(lengths)# Concatenate all words: ["red", "green", "blue"] => "redgreenblue" words = ["red", "green", "blue"] result = ____ for ____ in ____: ____ print(result)Solution

words = ["red", "green", "blue"] result = "" for word in words: result = result + word print(result)Create an acronym: Starting from the list

["red", "green", "blue"], create the acronym"RGB"using a for loop.Hint: You may need to use a string method to properly format the acronym.

Solution

acronym = "" for word in ["red", "green", "blue"]: acronym = acronym + word[0].upper() print(acronym)

Cumulative Sum

Reorder and properly indent the lines of code below so that they print a list with the cumulative sum of data. The result should be

[1, 3, 5, 10].cumulative.append(total) for number in data: cumulative = [] total += number total = 0 print(cumulative) data = [1,2,2,5]Solution

total = 0 data = [1,2,2,5] cumulative = [] for number in data: total += number cumulative.append(total) print(cumulative)

Identifying Variable Name Errors

- Read the code below and try to identify what the errors are without running it.

- Run the code and read the error message. What type of

NameErrordo you think this is? Is it a string with no quotes, a misspelled variable, or a variable that should have been defined but was not?- Fix the error.

- Repeat steps 2 and 3, until you have fixed all the errors.

for number in range(10): # use a if the number is a multiple of 3, otherwise use b if (Number % 3) == 0: message = message + a else: message = message + "b" print(message)Solution

- Python variable names are case sensitive:

numberandNumberrefer to different variables.- The variable

messageneeds to be initialized as an empty string.- We want to add the string

"a"tomessage, not the undefined variablea.message = "" for number in range(10): # use a if the number is a multiple of 3, otherwise use b if (number % 3) == 0: message = message + "a" else: message = message + "b" print(message)

Identifying Item Errors

- Read the code below and try to identify what the errors are without running it.

- Run the code, and read the error message. What type of error is it?

- Fix the error.

seasons = ['Spring', 'Summer', 'Fall', 'Winter'] print('My favorite season is ', seasons[4])Solution

This list has 4 elements and the index to access the last element in the list is

3.seasons = ['Spring', 'Summer', 'Fall', 'Winter'] print('My favorite season is ', seasons[3])

Key Points

A for loop executes commands once for each value in a collection.

A